Project Repo:

View the source code on GitHub

Note: Be sure to be in “Shayaun-Branch” not main.

This project is a SQL-style database built for educational and architectural exploration.

Project Overview:

This document provides a high-level overview of the database system, followed by detailed explanations of each subsystem, including key abstractions, design patterns, and architectural decisions.

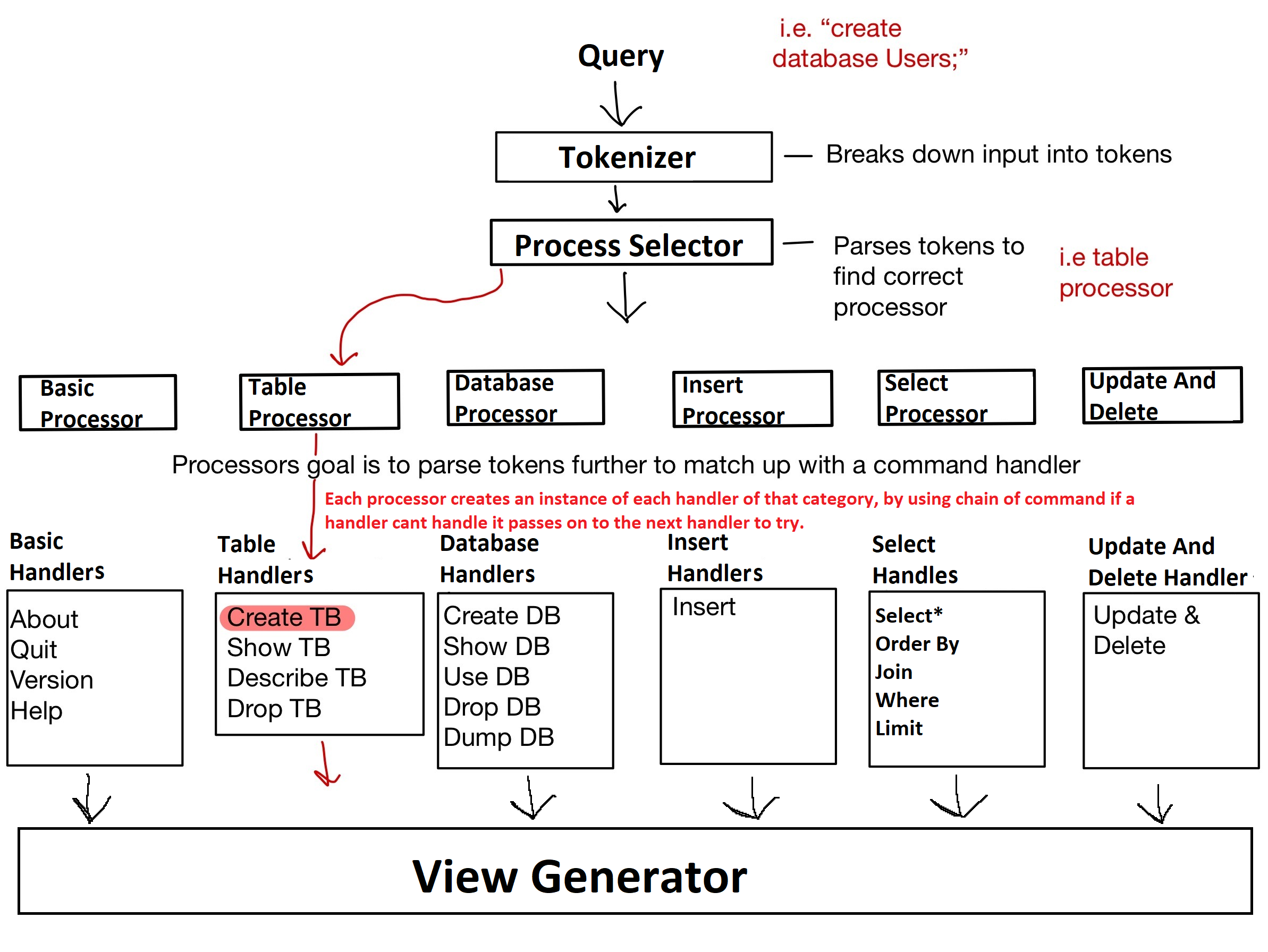

App Layer High level Walk Through:

We receive a query and hand it to our AppController object.

For example:

create table test1 (Schema);

The AppController then passes the input stream to our Tokenizer object.

The Tokenizer parses the input stream and breaks it down into a vector of tokens that our code can work with.

The responsibility of the AppController is to determine and delegate the work to the correct Processor.

It does so by parsing the token stream and selecting the appropriate processor based on the query type.

Each Processor sets up a Chain of Responsibility for handling a specific category of query (e.g., basic, table, database, etc.).

The Chain of Responsibility begins with one Handler that inspects the tokens and decides if it can handle the input.

If it cannot, it passes the responsibility to the next handler in the chain.

This process continues until either a handler is found that can process the query, or the chain ends.

The correct handler ultimately performs the necessary operations and passes a response string to the ViewListener object, which is responsible for rendering the appropriate output.

App Layer Low Level Walk Through:

In general we create each abstraction layer to follow “Single Responsibility Priniciple” this helps the code to be readable, scalable/maintainable , and low cognitive effort.

App Controller:

The first layer is our “App Controller” class, responsible for delegating query handling to the appropriate processor for a given query. While mainting the information of current database, state of program (running or not), and passing a ViewListener down the abstraction layers.

App controller uses a Tokenizer utility class to convert the input stream into a token sequence.

—

Processors:

The next abstraction layer is the processor layer, we have 6. “BasicProcessor”, “DataBaseProcessor”, “TableProcessor”, “InsertProcessor”, “SelectProcessor”, “UpdateandDelProcessor”.

Each processor’s single task is to setup the chain of responsibility for each type of query (i.g. Basic Query, DataBase Query, Table Query, or etc…).

This design follows the three core principles of good software: readability, scalability/maintainability, and low cognitive effort.

-

1. Readability

By breaking up the processors, each class handles a focused, well-defined task and stays around ~30 lines of code.

This makes each processor easy to read and understand in isolation, without requiring a full understanding of the entire system. -

2. Scalability & Maintainability

Having one large, monolithic processor that builds a giant Chain of Responsibility (CoR) would be difficult to scale or modify.

Every new command or change would require modifying a central block, increasing the risk of bugs and regressions.Instead, by pre-processing the tokens to select the appropriate processor early, we:

- Reduce unnecessary handlers loaded into memory

- Shorten traversal time through the chain (since unrelated handlers are skipped)

- Allow new processors to be added or modified independently — adhering to the Open/Closed Principle. “For example, to support a new query type (e.g., ALTER TABLE), we could introduce a new Processor and Handler pair without modifying existing code.

-

3. Low Cognitive Effort

Developers only need to understand one processor at a time,

rather than a tangled mega-handler with complex branching.

The system becomes more modular and easier to reason about, debug, and test.

Summary

This design methodology improves performance, modularity, and clarity. It aligns with core software engineering principles by ensuring each component has a single responsibility and a clear, self-contained scope.

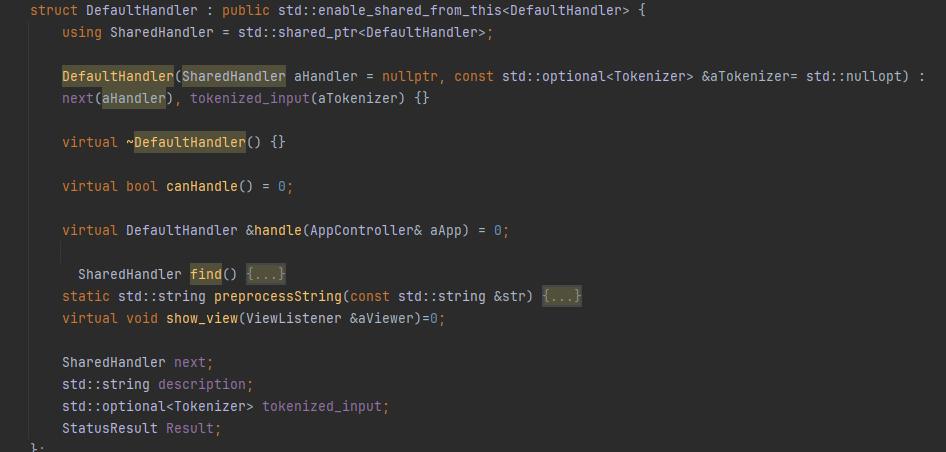

Handlers:

Handlers class sole responsibility is to do the actual work that the query needs as well as invoking a storage object to handle the saving of the database to memory, the Storage class is another abstraction layer for disk storage which I will talk about later.

All handlers are derived from a pure virtual base class, DefaultHandler, this allows us to achieve run time polymoriphsm which keeps our code clean, flexible, and less error prone.

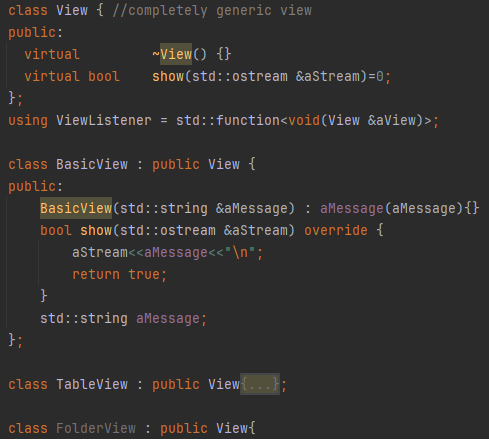

View-Generator:

The ViewListener is designed to respond to signals from command handlers, in our case receiving a string from the handler. Upon receiving the signal, it instantiates and renders the appropriate view.

This design cleanly decouples execution logic from view generation, improving modularity and maintainability. It also reduces code duplication by leveraging a shared interface: View serves as the base class for specific views like TableView and FolderView. It is up to the handler to choose the correct view.

For example, TableView is built to be data-driven — it operates solely on a collection of rows and doesn’t distinguish between different query types (e.g., SELECT *, JOIN, etc.). This abstraction means that as long as the correct row data is provided, the view can render it consistently, regardless of the query structure that produced it.

Database Layer Low Level Walk Through

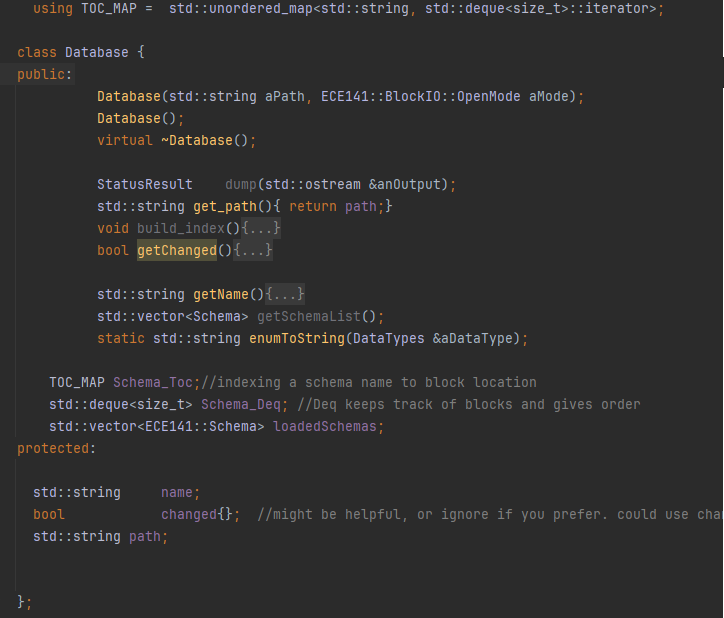

The Database class represents a high-level interface for interacting with stored database contents. It operates in two distinct modes depending on how it is constructed:

- Open mode: Loads a preexisting database from disk by invoking the

Storagelayer and populating in-memory structures like the Table of Contents (TOC) map and the schema list. - Create mode: Initializes a new database file, writing an empty TOC block to disk.

The core responsibility of this class is to maintain the mapping between schema names and their physical locations on disk — while also managing a live list of Schema objects in memory. When a query like CREATE TABLE is executed, a new schema is built and registered here. Conversely, on startup, previously stored schemas are loaded into memory by parsing the TOC block.

We use a custom TOC_MAP, which maps a schema name (hashed) to a deque iterator — this enables both fast lookup and ordered storage of schema blocks. The associated Schema_Deq deque holds the block positions of all loaded schemas. This makes it easy to traverse, update, and write back schemas in a deterministic order.

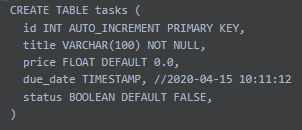

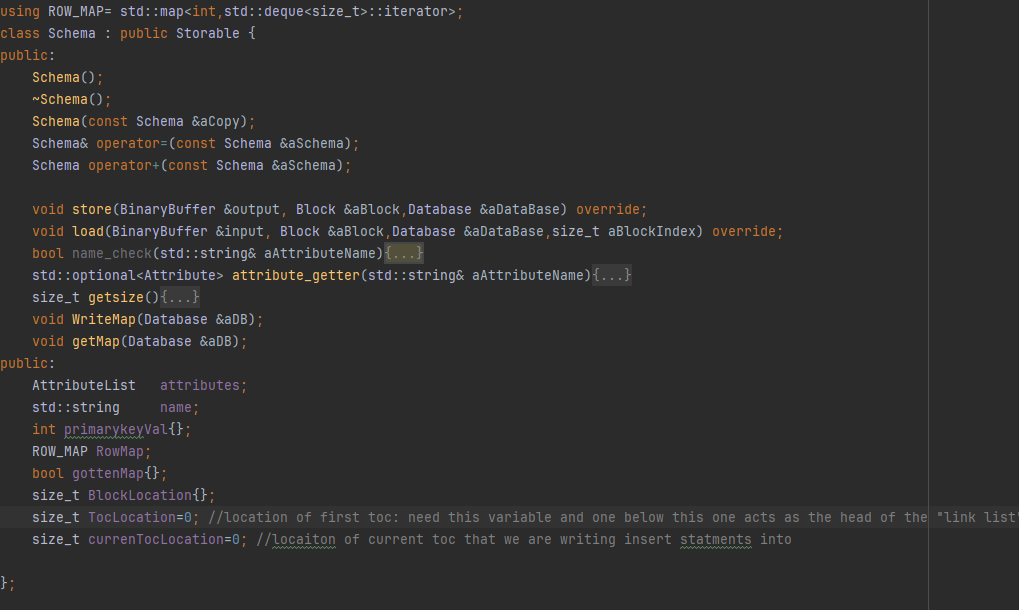

Schema

A Schema object defines the layout of a table — it stores metadata such as attribute names, data types, primary key status, nullability, and defaults. Schemas are generated by parsing CREATE TABLE statements and are used later to validate INSERT or SELECT operations.

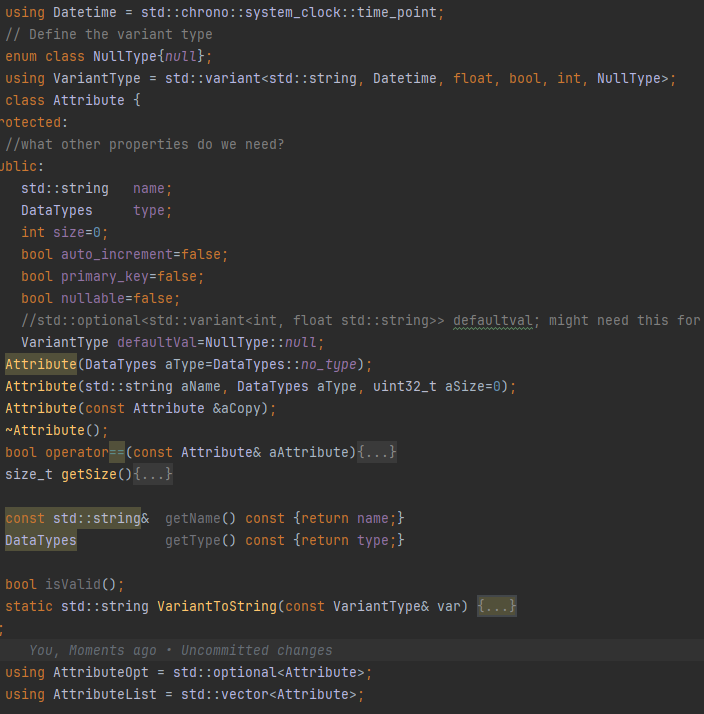

Attributes

Each Attribute defines one column of a table. Its structure captures:

- Field name

- Data type (

int,varchar,float, etc.) - Field length

auto_increment,primary_key, andnullableflags- Default value (as a

VariantType)

By encapsulating attribute metadata this way, your system is able to fully reconstruct or validate table structure on load.

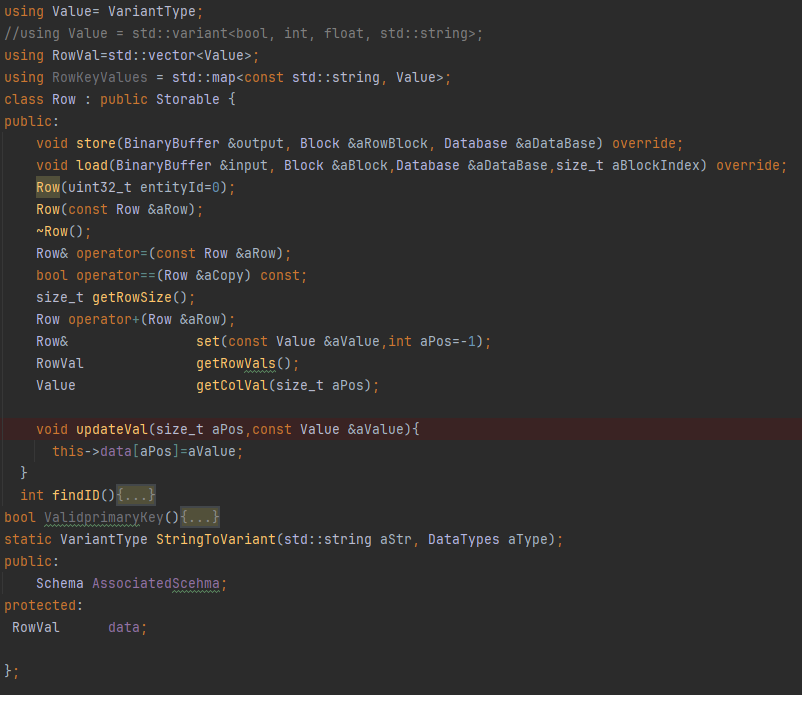

Rows

The Row class represents an individual record within a table. It contains a vector of typed VariantType values, one for each column. Rows are associated with a schema to interpret their contents.

Rows support serialization through the store() method (writing variant-typed data to a block payload), and deserialization with load() — where column types are looked up from the associated schema.

This class also defines utility operators for equality, merging (operator+), and indexed access, enabling flexibility in query processing or JOIN logic.

This layer demonstrates modular responsibility, clear ownership boundaries, and data model extensibility — with the Schema, Attribute, and Row classes each focused on a single domain concern. The use of variants, schema-bound row deserialization, and TOC-mapped block locations reflects a deliberate and scalable database design.

Memory Layer High Level Walk Through:

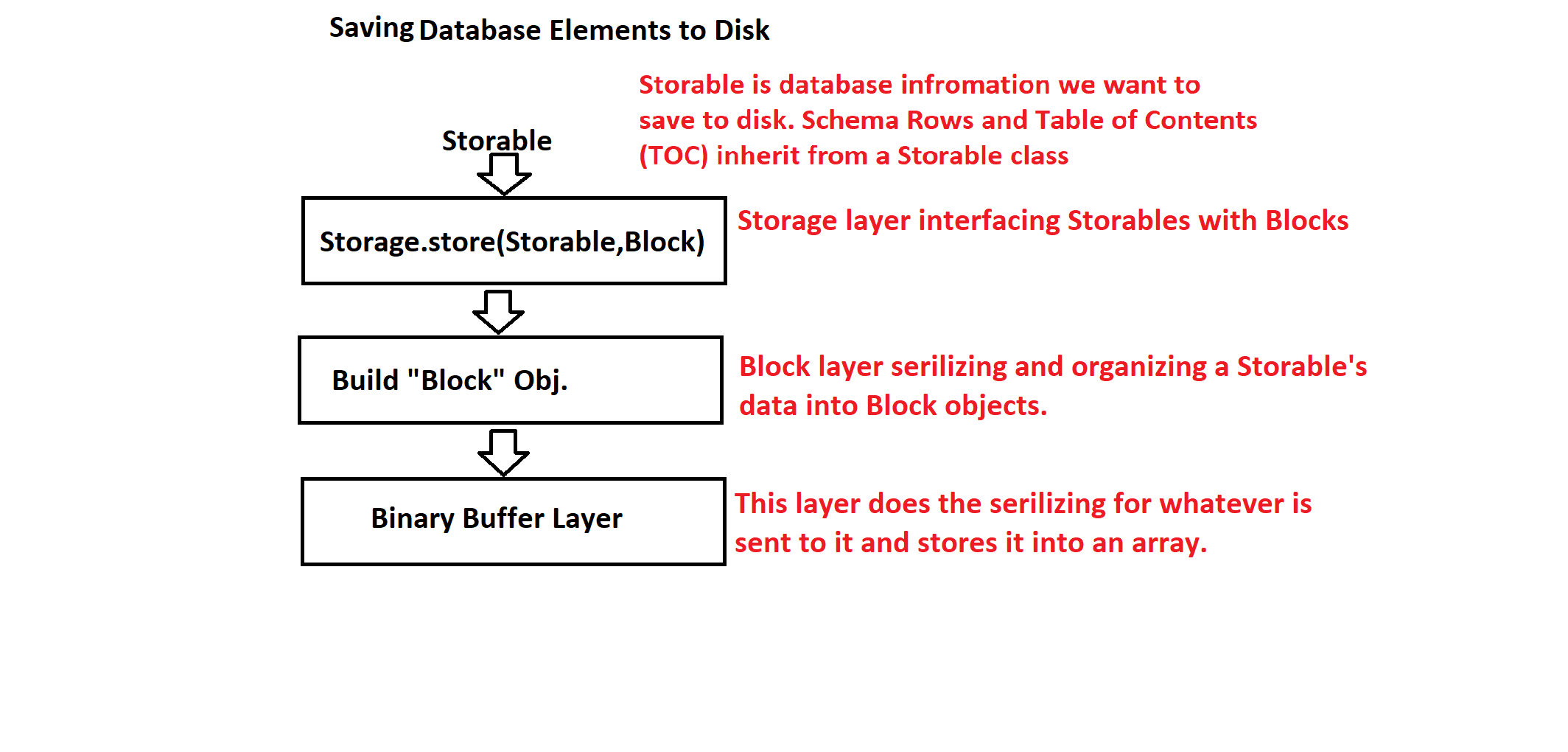

For Saving to Disk:

The storage layer begins with a Storage object. This class serves as the interface between high-level database objects (like Schema, Row, or Table of Contents) and low-level binary blocks written to disk.

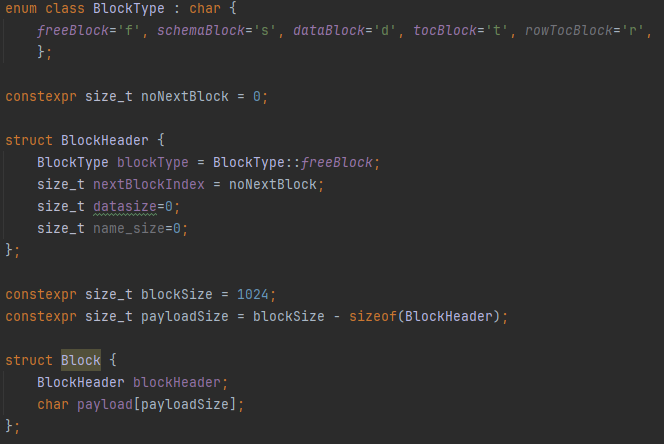

Each Storable object implements its own store() and load() methods, which serialize or deserialize themselves using a BinaryBuffer, writing into a Block object. Blocks are fixed-size (1024 bytes) and contain a header (metadata like block type, name length, and data size) followed by a payload section used to hold serialized binary data.

For example, when storing a Schema, the block’s header records that it’s a schemaBlock, along with the schema name size and total data size. The payload includes the attribute list, primary key data, and any other schema metadata. The BinaryBuffer handles writing this data into the block in a platform-independent way.

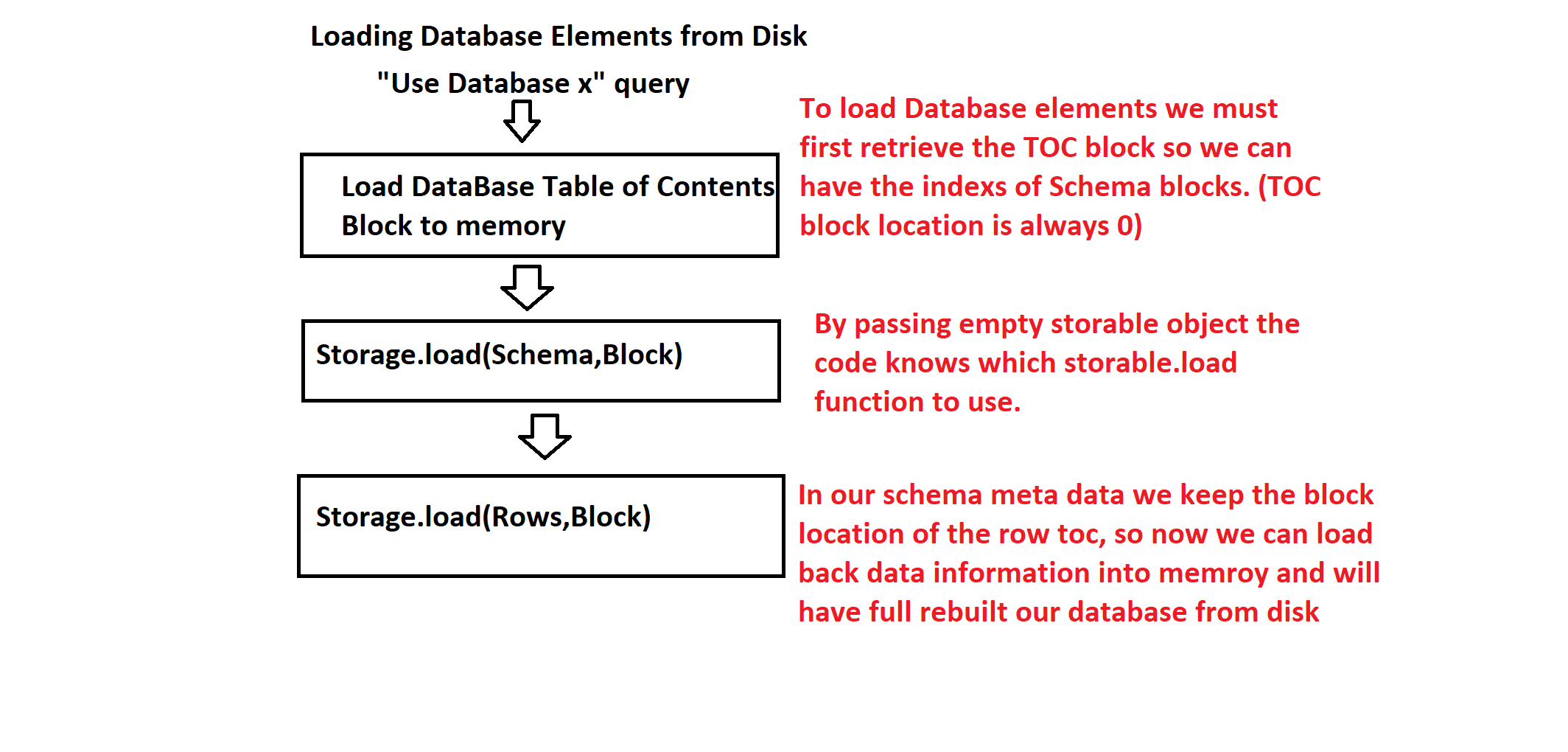

For Loading from Disk:

When opening an existing database, we again start with a Storage object. This time, the first block we load is the Table of Contents (TOC) block, which maps schema names (stored as hashes) to their physical block locations. After parsing the TOC, we load each Schema block and any related row index blocks as needed.

Memory Layer Low Level Walk Through:

Storage

The Storage class adheres to the Single Responsibility Principle (SRP) by acting solely as the interface between high-level database objects and low-level binary file I/O. Its primary role is to serialize and deserialize objects (via the Storable interface) into fixed-size blocks for persistent storage. It delegates all file access to the BlockIO class, keeping storage logic decoupled from physical I/O operations.

In handling data conversion, the Storage class uses a BinaryBuffer helper to convert between in-memory variants and byte-level representations. Notably, the writeVariant method leverages the Visitor pattern (std::visit) to write different VariantType values (e.g., int, string, float, bool) in a type-safe, extensible way. This design simplifies variant handling and ensures the buffer logic remains modular and easy to extend as new types are added.

This layer abstracts the process of serializing objects to disk using fixed-size blocks, enabling persistent storage of schema, rows, and metadata.

Overall, the Storage class provides a clean, focused abstraction for object persistence while offloading concerns like view logic, query processing, or block management to other layers.

Block Layer

At the block level, the system is designed around a modular, extensible interface for writing and reading persistent data structures to disk. Every object that can be serialized to storage (e.g., Schema, Row, TOC) implements the Storable interface, giving each class ownership of how it packs and unpacks its data into a fixed-size block structure.

This approach enables polymorphic storage logic, the Storage class doesn’t need to know what it’s storing, only that it adheres to the Storable contract. This promotes encapsulation by pushing block-specific serialization logic into the object itself, instead of centralizing it in the storage layer.

For example, the Schema class implements its own store() and load() methods. When storing, it encodes its metadata (e.g., schema name, attribute list, TOC pointers) into a binary buffer. Each attribute is serialized field-by-field, including its name, data type, flags, and default value. defaultVal is a variant, written using the Visitor pattern via std::visit. This keeps the logic type-safe and scalable as more types are added.

Block chaining is also handled at this level. Large schema row maps that can’t fit in a single block are automatically split across multiple index blocks, which are chained using nextBlockIndex in the block header. The WriteMap() method handles this transparently. On load, getMap() reconstructs the full map by traversing the chain — a design pattern similar to FAT tables or inode chains in filesystems.

Together, this design reflects strong object-oriented practices, enabling per-object control over persistence while abstracting away raw disk mechanics through block-based encoding.

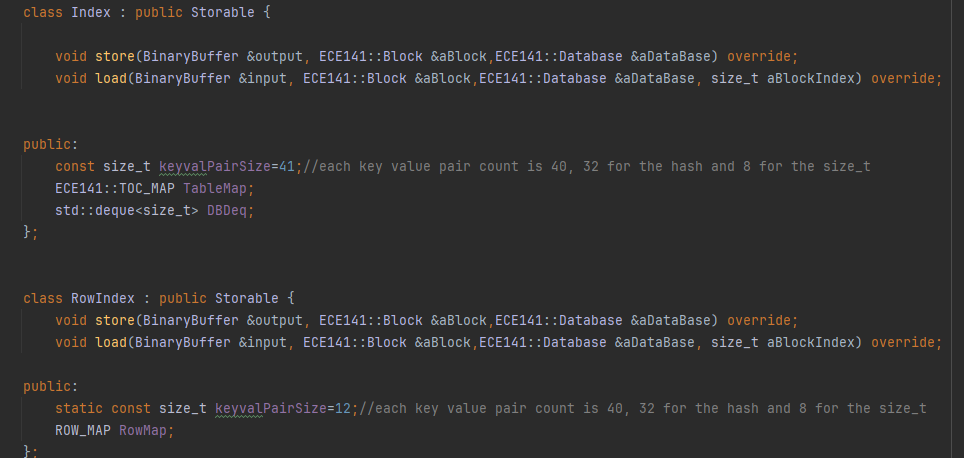

Table of Contents

The TOC (Table of Contents) layer is responsible for mapping logical database identifiers (like schema names or row primary keys) to their physical locations on disk. This logic is encapsulated in two classes: Index for Schema-level TOC, and RowIndex for Row-level TOC blocks. Both implement the Storable interface, making them first-class participants in the block system and fully compatible with the storage pipeline.

The Index class manages schema metadata. It hashes each schema name using SHA256 and stores a key–value pair: (schema hash → schema block location). This mapping is serialized into a dedicated TOC block, with each entry written in a consistent binary format. On load, it rehydrates the mappings by reading the block, loading the associated schema object, and verifying the integrity of each entry by rehashing the schema name and comparing it with the stored hash. This adds a lightweight form of integrity checking without needing a full checksum system.

Internally, Index maintains:

TableMap: a map from schema name to its location within astd::dequeof block positionsDBDeq: a deque storing block locations of loaded schemas

The RowIndex class operates similarly but focuses on rows within a specific schema. It serializes primary key → row block location mappings, which are split into fixed-size chunks if the row map exceeds the payload size of a block. This design ensures scalability as datasets grow. On load, RowIndex repopulates the in-memory row map and updates the owning schema’s block list (Schema_Deq).

Having a Row Index is especially usefull for fast Inserts, JOINs, and Selects since we do not need to do full memory look up to find blocks.

By treating TOC blocks as Storable objects and applying consistent logic across schema and row indexing, this layer stays modular, extensible, and easy to reason about. It demonstrates encapsulation, consistent data ownership, and a clean separation of metadata handling from actual data storage.

This version aligns with how technical readers think: responsibilities, internal invariants,

More Features:

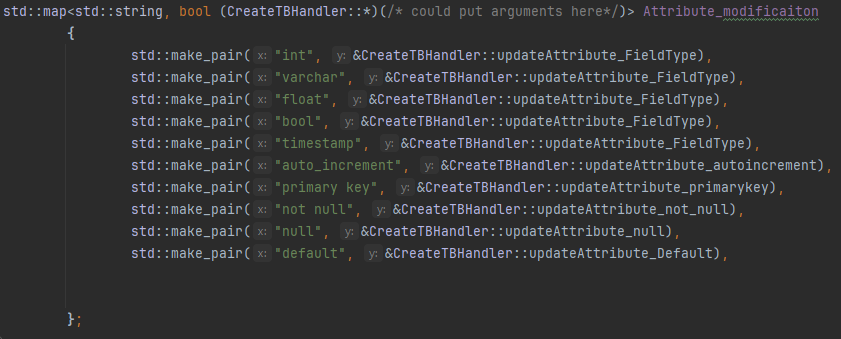

1.) Instead of hardcoding parsing logic for every keyword, we used a std::map to flexibly dispatch handler functions based on parsed tokens. Which not only simplifies parsing logic but also makes the system easily extensible. For compound keywords like not null, the parser looks ahead and combines tokens to check for those keys in the map as well. Each function encapsulates the logic to update a specific field in the attribute object, so parsing and attribute-building stay cleanly separated.

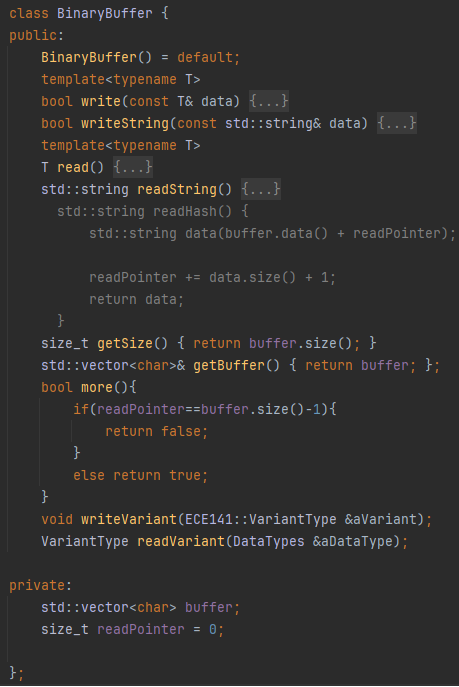

2.) The BinaryBuffer class is a lightweight, type-safe serialization utility that enables writing and reading raw binary data (including strings and variant types) to and from an internal std::vector

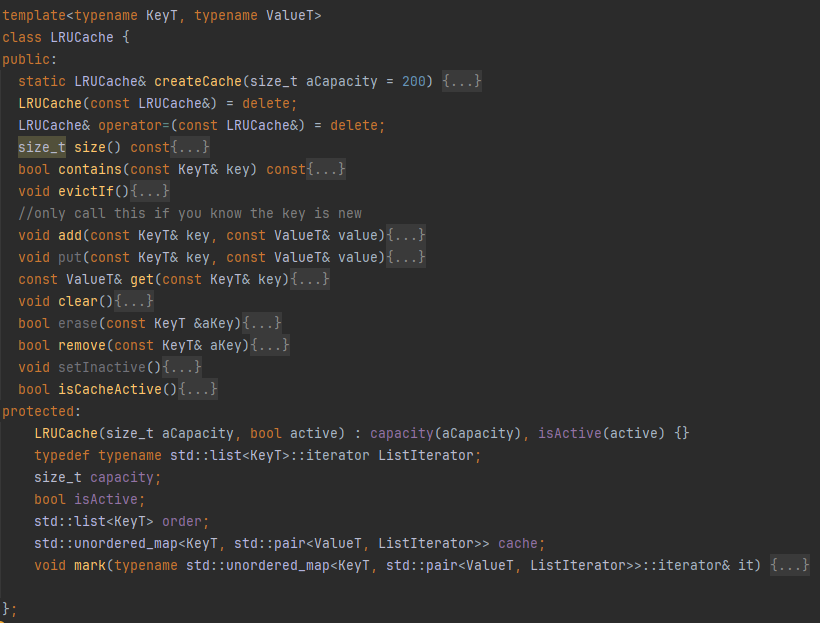

3.) The LRUCache class is a high-performance, type-generic cache that uses a Least Recently Used (LRU) eviction policy to manage memory efficiently. It combines a std::list to maintain access order with an unordered_map for constant-time lookup and insertion, ensuring that recently accessed data remains readily available while older, unused data is evicted when capacity is reached. This pattern is especially useful in database systems for caching frequently used rows, schemas, or metadata, reducing redundant disk access and improving runtime efficiency. The cache also includes control features like activation toggling (isActive) and a singleton-style createCache() factory, giving the developer flexibility in when and how caching is applied. Overall, it introduces a modular and efficient way to optimize performance without invasive changes to the core logic.

Future Work / Weaknesses

- Work on minimizing sending big objects into function calls.

- Handlers still do a lot of the work, consider breaking up the work into helper functions improve readablity.

- Work on remoting.

- Audit class members and refactor public fields to accessor/mutator methods where appropriate.

- Work on #include and circulary dependcy issues.